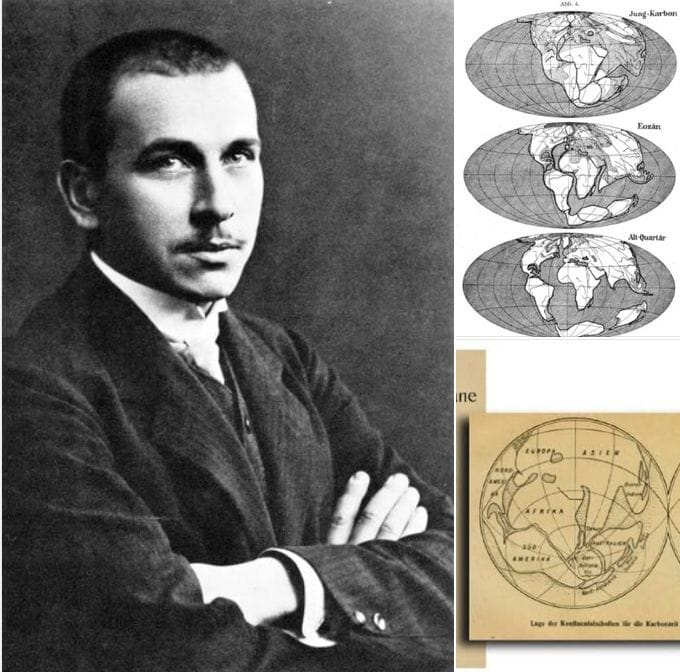

On January 6, 1912, Alfred Wegener— at the time a 32-year-old meteorologist and geophysicist—delivered a lecture to the Geological Association in Frankfurt am Main. It was the first time he went public with a his new idea explaining how “large-scale features of the Earth’s crust” formed over time. Four days later he presented his “theory of horizontal displacement of the continents” in Marburg.

His idea was simple: in the geological past, there was a single land mass, which he called Pangaea (“all Earth”). This supercontinent later broke apart as the continents gradually moved to their present positions.

His theory will appear in expanded form in 1915 as “The Origin of Continents and Oceans.”

Wegner faced far more criticism than support, with some opponents even mocking his idea as “continental drift.

He was not the first to propose that continents like South America and Africa were once united, but in his book he provided geological, paleontological and even biological evidence (like the same species of snails—not very mobile animals—living in continents separated by an entire ocean) and a theoretical mechanism how continents could move.

Wegener’s theory held that continents, made of relatively light crustal material, move through denser basaltic oceanic crust much like icebergs through water. This motion, he argued, forms mountains at their edges as they “plowed” through the Earth’s surface.

However, Wegner faced far more criticism than support, with some opponents even mocking his idea as “continental drift.”

Wegener was unable to provide a convincing mechanism capable of moving entire continents. He suggested the Moon’s gravitational pull and tidal forces as possible drivers and at first relied on uncertain coastal surveys, proposing drift rates of several meters per year—claims that were quickly debunked by his critics.

In many important respects, the theory of continental drift was erroneous. In reality, it is not individual continents that move, but tectonic plates composed of continental and oceanic crust. The forces driving this motion originate within the Earth, primarily mantle convection and slab pull, rather than from the outside.

But Wegener’s work helped popularize the idea of mobile continents among both the scientific community and the general public.

South African geologist Alexander du Toit (1878–1948) quickly adopted continental drift to explain the striking geological similarities between South America and Africa.

Swiss geologist Émile Argand (1879–1940), influenced by Wegener’s ideas, interpreted mountain building as the result of continents colliding and oceans closing. His work helped explain why fragments of continental crust and oceanic sediments are found together in mountain ranges.

Beyond science, continental drift even entered popular culture: horror and science-fiction writer H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937) mentions an ancient supercontinent inhabited by the Great Old Ones in one of his stories (At the Mountains of Madness, 1936).

Wegener died in 1930, aged just 50, during an expedition in Greenland. Only decades later will his ideas pave the way for a new theory: modern plate tectonics.

Further reading:

Why Plate Tectonics was not invented in the Alps: